JAZZ CRITIC

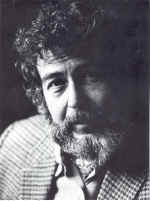

Whitney Lyon Balliett

April 17, 1926 - February 1, 2007 - Manhattan

Jazz Reporter

Known for Poetic Prose

By Adam Bernstein

Washington Post Staff Writer

Friday, February 2, 2007; B07

Whitney Balliett, 80, a jazz reporter who spent more than four decades

writing thousands of graceful and definitive stories for the New Yorker

magazine and helped create one of the finest jazz programs on

television, died February 1, at his home in Manhattan, N.Y. He had liver

cancer.

Jazz critic and poet Philip Larkin described Mr. Balliett as "a

writer who brings jazz journalism to the verge of poetry." Dan

Morgenstern, director of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers

University, called him "the greatest prose stylist to ever apply

his writing skills to jazz."

Mr. Balliett began writing a regular jazz column for the New Yorker in

1957. To convey the essence of music and musicians, he avoided technical

terms. He considered himself an "impressionist" when he wrote

about musicians because music itself is fleeting, so "transparent

and bodiless." Jazz in particular, he wrote, had "odd

non-notes and strange tones and timbres."

In his observations, he created portraits of entertainers in action. As

an amateur drummer, he had a particular appreciation for skilled

drummers.

Writing of one of his idols, the drummer Sidney

"Big Sid" Catlett, he said, "One was transfixed by

the easy motion of his arms, the pulse-like rigidity of his body, and

the soaring of his huge hands, which reduced the drumsticks to

pencils."

One of Mr. Balliett's most-anthologized pieces was his 1962 profile of

clarinetist Pee Wee Russell, titled "Even His Feet Look Sad."

As for Russell's music, Mr. Balliett wrote: "No jazz musician has

ever played with the same daring and nakedness and intuition. His solos

didn't always arrive at their original destination. He took wild

improvisational chances and when he found himself above the abyss, he

simply turned in another direction, invariably hitting firm ground.

"His singular tone was never at rest. . . . Above all, he sounded

cranky and querulous, but that was camouflage, for he was the most

plaintive and lyrical of players."

Whitney Lyon Balliett, the son of a businessman, was born April 17,

1926, in Manhattan. While attending the private Phillips Exeter Academy

in New Hampshire, he began what he called his "erratic noncareer as

a drummer" after hearing a jam session on a Sunday afternoon at

Jimmy Ryan's club on New York's West Side.

"The famous old New Orleans drummer Zutty Singleton was

hypnotic," he later wrote of the experience for the Atlantic

Monthly. "He moved his head to the rhythm in peculiar ducking

motions, shot his hands at his cymbals as if he were shooting his cuffs,

hit stunning rim shots, and made fearsome, inscrutable faces, his

eyelids flickering like heat lightning."

After graduating from Cornell University in 1951, he wrote about jazz

for the Saturday Review while working as a proofreader for the New

Yorker. William Shawn, an admirer of jazz pianist Fats Waller, gave the

young staff writer a jazz column in 1957.

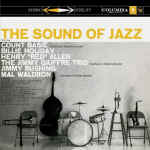

The same year, he and jazz critic Nat Hentoff helped create the CBS-TV

program "The

Sound of Jazz," an offshoot of the series "The Seven

Lively Arts."

The jazz show, hosted by New York Herald Tribune columnist John Crosby,

brought to millions of homes such eclectic performers as Billie Holiday,

Count Basie, Gerry Mulligan and Thelonious Monk. The program also

twinned unlikely pairings of musicians, such as Russell and Jimmy

Giuffre, clarinetists of two very different generations and styles.

Eric Larrabee wrote in Harper's magazine that "The Sound of

Jazz" was the "best thing that ever happened to

television." Columbia Records produced an album of the show's

performers, and a video of the program was released in the mid-1980s.

Jazz critic John S. Wilson, writing in the New York Times in 1985, said

that "putting Monk on national television at a time when, to the

extent the general public knew of him at all, he was apt to be

considered weird and possibly menacing, was a courageous and positive

act."

Mr. Balliett contributed short articles for the New Yorker's Talk of the

Town section as well as book, film and theater reviews. He also wrote

poetry. He left the magazine staff in 1998.

Collections of his New Yorker writings were published frequently over

the years. His books included "American Singers" and

"American Musicians." One massive volume, subtitled "a

Journal of Jazz," came out in 2000.

Reviewers noted that Mr. Balliett's taste was more traditional than

avant-garde, and he tended to overlook more contemporary players, but he

liked to approach all music with a degree of curiosity. He also had a

reputation for writing sympathetically about his subjects, often letting

them speak for paragraphs at a time to convey their rhythm and

personality.

"You have to look at it from the musicians' point of view," he

told the Times of London in 1993. "Often they don't get paid more

than the union minimum or they've been on the road. I once traveled with

Duke Ellington's orchestra, for about five days, and I couldn't believe

it. Jesus! You don't know where you are, you have no sense of time or

place, you can't sleep right. How these guys do it for so long, I don't

know."

His marriage to Elizabeth King Balliett ended in divorce.

Survivors include his wife of 41 years, landscape painter Nancy Kraemer

Balliett of Manhattan; three children from his first marriage, Julie

Rose of Accord, N.Y., Blue Balliett of Chicago and Will Balliett of

Manhattan; two sons from his second marriage, Whitney L. Balliett Jr. of

Natick, Mass., and Jamie Balliett of Erie, Colo.; a brother; a

half-sister; and seven grandchildren.

Photo from

Big Sid Catlett

Pee Wee Russell

Nat Hentoff

LINKS