Daniel Bejar

______________________

Historyís Tangled Threads

By FERGUS M. BORDEWICH

Published: February 2, 2007

FEW aspects of the American past have inspired more colorful mythology than the Underground Railroad. Itís probably fair to say that most Americans view it as a thrilling tapestry of midnight flights, hairbreadth escapes, mysterious codes and strange hiding places.

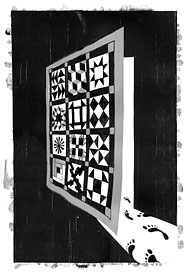

So itís not surprising that the intriguing (if only recently invented) tale of escape maps encoded in antebellum quilts" enshrined in a metastasizing library of childrenís books and teachersí lesson plans and perhaps even in a Central Park memorial to Frederick Douglass" should also seize the popular imagination.

But faked history serves no one, especially when it buries important truths that have been hidden far too long. The "freedom quilt" myth is just the newest acquisition in a congeries of bogus, often bizarre, legends attached to the Underground Railroad. Despite a lack of documentation, tales of actual tunnels through which fugitives supposedly fled persist in communities from the Canadian border to the Mason-Dixon Line.

Popular songs associated with the underground rarely withstand scrutiny, either. Recent research has revealed that the inspirational ballad "Follow the Drinking Gourd" perhaps the single best-known "artifact" of the Underground Railroad" was first published in 1928, and that much of the text and music as we know it today was actually composed by Lee Hays of the Weavers in 1947. Nor do its "directions" conform to any known underground route.

Legend has also elevated to nearly superhuman status the underground conductor Harriet Tubman, typically claiming that she led north more than 300 slaves. The actual number was closer to 70, according to a Tubman biographer, Kate Clifford Larson. The truth takes nothing away from Tubman, a remarkable woman by any measure, but her deification as the embodiment of the Underground Railroad has obscured the work of many lesser-known African-American activists "among them New Yorkís David Ruggles, who organized the cityís underground in the 1830s and helped more than 600 former slaves to freedom.

The notion of maps hidden in quilts surfaced in the 1980s, in a childrenís book, according to a quilting historian, Leigh Fellner, who has shown that many of the patterns supposed to contain "coded" directions for fugitives date from the 20th century.

Such fictions rely for their plausibility on the premise that the operations of the Underground Railroad were so secret that the truth is essentially unknowable. In fact, there is abundant documentation of the undergroundís activities to be found in antebellum antislavery newspapers, narratives of escape written by former slaves and the recollections of participants recorded after the Civil War, when there was no longer danger of reprisal. None mention quilts, tunnels or, with the rarest of exceptions, any hiding place more exotic than a barn or attic.

Most successful fugitives were enterprising and well informed. The vast majority had little need for coded maps, since they came from the border states of Maryland, Virginia and Kentucky, just a few daysí or hoursí walk from the nearest free state.

The Underground Railroad provided shelter, transportation and guides, but through most of the North its work was hardly secret. Abolitionist newspapers reported news of fugitives in detail "their passage through town, the names of people whoíd assisted them. In some places, activists distributed handbills announcing what they were doing and how many fugitives they had helped. Jermain Loguen, the African-American leader of the underground in Syracuse, advertised his address in local newspapers as an aid to freedom-seekers.

The larger importance of the Underground Railroad lies not in fanciful legends, but in the diverse history of the men and women, black and white, who made it work and in the far-reaching political and moral consequences of what they did. The Underground Railroad was the nationís first great movement of mass civil disobedience after the American Revolution, engaging thousands of citizens in the active subversion of federal law, as well as the first mass movement that asserted the principle of personal responsibility for othersí human rights. It was also the nationís first interracial political movement, which from its beginning in the 1790s joined free blacks, abolitionist whites and sometimes slaves in a collaboration that shattered racial taboos.

During the long dark night of Jim Crow politics, these deeper truths of the Underground Railroad were suppressed: in a nation committed to segregation and blind to racism, the story of a politically radical, biracial movement led in part by African-Americans was far too subversive to accept.

Eye-catching quilts and mysterious tunnels satisfy the human penchant for easily digestible history. Myths deliver us the heroes we crave, and submerge the horrific reality of slavery in a gilded haze of uplift. But in claiming to honor the history of African-Americans, they serve only to erase it in a new way.

Americans still have a difficult time talking about race and slavery, and the Underground Railroad deserves to be part of the national discussion. It forced Americans to think about slavery in new ways, by delivering tens of thousands of former slaves into Northern communities.

There, for the first time, whites began to learn firsthand about the realities of slavery "the physical and emotional cruelties, the ruptured families, the abuse of enslaved women" and to empathize with black Americans as people like themselves, with the same human needs and desires, the same vulnerabilities, the same devotion to family and faith.

In an age when self-interest has been elevated in our culture to a public and political virtue, the Underground Railroad still has something to teach: that every individual, no matter how humble, can make a difference in the world, and that the importance of oneís life lies not in money or celebrity, but in doing the right thing, even in silence or secrecy, and without reward. This truth doesnít need to be encoded in fiction in order to be heard.